Achieving Justice for Imam Jamil:

A Battleline For All of Us

|

|

|

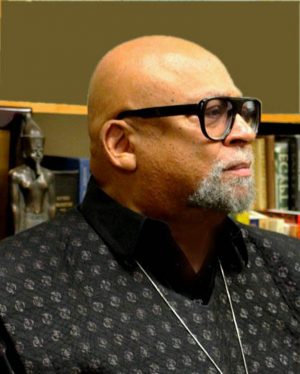

| Dr. Maulana Karenga |

|

He came into the consciousness of his people and in the cross-hairs of the oppressor on the blood-stained battlefields and battlelines of the Black Freedom Movement of the 1960s. The media called Imam Jamil Al-Amin, H. Rap Brown then, but we just called him Rap because of the hard hitting, defiant, rhythmic and righteous way he described and condemned our oppressor and oppression and praised our people and challenged them to stand up, step forward and continue the liberation struggle.

We had met first when he and other national and local leaders came to speak at the 'African American Cultural Center' (Us) headquarters at our annual Uhuru Day Rally to commemorate the Watts Revolt in August 1966. We met briefly also at the SNCC headquarters in Atlanta when Us and SNCC were exploring incorporating Watts as a freedom city separate from Los Angeles. We had ample time to talk when he came to speak at a Free Huey Rally at the Los Angeles Sports Arena that Us had played a key role building support for and organizing within the context of the Black Congress, a Black united front, including the major groups in the L.A. area. He and I spoke at the rally, along with a long list of Black leaders and activists, as well as the Mexican leader, Reies Tijerina. Also, we had stood together against taking Custer stands with the police at the event, and I had sent Tommy Jacquette-Halifu, a founding member of Us, to provide security for him to the airport. Halifu was a man of the people and I had also sent him to the Bay area with Kwame Ture to speak at Hunter's Point and elsewhere. He had built a strong relationship with both. May the work Halifu and Kwame did and the good they brought last forever and always be a lesson and inspiration to us all.

|

|

Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Toure) and H. Rap Brown (Imam Jamil Al-Amin)

|

Rap was his battle name, and his words were, as we say of Kawaida philosophy, a shield and sword, a pillow of peace and a constant call to righteous and relentless struggle. Long before the art of rappin' was redefined as only a young people's music, it was a whole people's way of talking, telling truth, making sense, doing word magic with sayings and songs or running down a love proposal or program in smooth, cool and powerfully persuasive ways, i.e., making a case for togetherness in both personal and collective ways. And Rap was a master rapper, skilled in the spoken word, speaking rhythmically without rhyme, but with compelling reason; speaking truth to the people and to power, calling for an increase and expansion of the righteous and relentless struggle we as a people were waging for our liberation and a higher level of human life.

Historian Vincent Harding, speaking at a support rally for Imam Jamil in March 2012, said that Imam Jamil had, even at an earlier age, recognized and accepted the responsibility of youth to make a better world. Moreover, he said, Imam Jamil knew that youth "must develop themselves and become leaders in the building of a just and fair society." And that he has spent "his life working on the creation of something better, something just for all of us in this country and in the world." Indeed, he did this during the Black Liberation Movement and continued with his work after the Movement as a respected and loved Imam waging jihad, righteous struggle, on the spiritual and social levels and contributing greatly to the advancement of Black and human freedom.

In the 60s when they tried to muzzle and mute his voice of struggle, and of teaching the unvarnished and victorious truth, he would not be cowered, cut off or calmed down. "Let Rap, rap" we shouted. "Teach, Rap. Go on and rap Rap" we called out as he lit fire to falsehood, exposed the hidden horrors of the oppressor and raised high the praise for the people and the urgent need to continue and intensify the struggle. And now they seek to muzzle and mute his voice again. In 2002, he was falsely convicted of murder of a police officer and wounding another and sentenced to life in prison. Imam Jamil has always asserted and maintained his innocence. And there were holes and inconsistencies in the prosecutor's narrative of conviction: the eyes and height description of the shooter; the wounded officers' statement of having wounded the assailant, but no wounds were on Imam Jamil; a blood trail, but no blood on or from Imam Jamil; what was seen as a planted gun at the scene of Imam's arrest; reports of police pressuring of the witnesses; and a confession later of someone who said that he was the shooter.

|

|

|

Imam Jamil Al-Amin

|

Having locked Imam Jamil down in a Georgia State prison, the state and federal government secretly transferred him out of state to a supermax underground federal person in Florence, Colorado without the knowledge of his family or lawyer on August 1, 2007. This was strange and suspicious because Imam Jamil was not convicted of a federal crime, but a state crime and thus unless there was some problem of space or of special circumstances, he should have remained in the state of the conviction. But it was not for reasons of space and there was no justification of special circumstances, but rather an expression of the governmental desire to capture, isolate and break him as was their long-term intention and as further demonstrated, by their transferring him to another federal prison in Arizona. Therefore, the current righteous struggle to return Imam Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin back to Georgia and bring him out of the brutalizing isolation in the federal prison in Arizona, to get for him the medical treatment he urgently needs, and to free him from wrongful imprisonment is a struggle for justice in a most compelling and comprehensive sense.

Clearly, his trial was grossly flawed and his conviction was deeply wrongful. His targeting and imprisonment was political. His transfer from a prison in Georgia for a state conviction to federal prisons in Colorado and Arizona and being placed in solidarity confinement for 8 years is vindictive, vicious and designed to isolate him from family, community and legal counsel, and punish and break him. The refusal to allow journalists and academics to see and interview him is to muzzle him and eliminate the regular monitoring and checking on their savage treatment of him. And the denial of adequate and appropriate treatment for him is inhumane, a violation of his human rights and creating conditions for his death. Thus, we must see and engage this as a moral obligation to resist and reverse these unjust and evil actions.

Imam Jamil tells us from the beginning that we must not expect justice to be given to us without struggle in the midst of an unjust and evil society. Therefore, he urges us to constantly struggle to bring into being the good world we all want and deserve. He says "I can find only three places for a righteous man in an evil society: on the battlefield fighting his enemy; in a cell imprisoned by the enemy; or in his grave free from his enemy. Outside this, I find only hypocrisy." Immediately, this calls to mind Min. Malcolm's teaching that "Wherever a Black man (woman) is, there is a battleline." Indeed, Haji Malik continues saying, "We are living in a country that is a battleline for all of us." So, as we said in the Sixties, even if you, yourself, are not at war, you are in a war, a war being waged against you, your people and against people and things righteous, revolutionary and resistant. And thus, it behooves us to come to the battlefront conscious, capable and committed. Also, as we said then and must know as true now, there can be no half-stepping and no compromised commitment, for the brutal nature of our oppression and the evil character of our oppressor will not permit it.

Finally, Imam Jamil tells us that we must continue the struggle, not only to free him, but also ourselves and the world. He says, "We have to see ourselves as the authors of a new justice. And wherever we see injustice and tyranny, we must (stop) it." Our task, he states, is "to make the world more humane." Indeed, he concludes, "That has to be the role of any revolutionary or any person that considers himself (herself) revolutionary." And we of Us say again and again of our righteous and relentless struggle to bring good in the world, "If not this, then what? And if we don't do it, who will?"

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.Official Kwanzaa Website.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.

|

Comment by Bilal Mahmud المكافح المخلص on April 29, 2019 at 4:35pm

Comment by Bilal Mahmud المكافح المخلص on April 29, 2019 at 4:35pm

![]()

You need to be a member of Oppressed Peoples Online Word...The Voice Of The Voiceless to add comments!

Join Oppressed Peoples Online Word...The Voice Of The Voiceless